The peace stone that was pulled by hand from Boston to Washington never made it to Arlington National Cemetery, its intended destination, and instead was hauled away by a tow truck yesterday after demonstrators gave it to the U.S. Park Police for safekeeping.

The organizers of the Stonewalk are members of the Peace Abbey, a Sherborn, Mass., interfaith center that promotes world peace. They had planned the pilgrimage for more than a year but arrived in town without authorization to place the granite memorial dedicated to civilian war victims in Arlington National Cemetery. Congress has to approve any additions to the cemetery and had not done so by yesterday.

A group of about 150 people escorted the one-ton memorial atop a 1,500-pound caisson partway across Memorial Bridge at noon yesterday before dropping the draw bars and leaving it in the roadway. They had been heading for the Lady Bird Johnson Park on the Virginia side of the bridge for a final rally when they abandoned the caisson.

“We stand here at the midpoint of the bridge to temporarily conclude that this stone has no home,” said Lewis Randa, chairman of the memorial project. “We are temporarily suspending taking the only memorial to civilian war victims to Arlington.”

Randa said the group members had found that their best friends on the 500-mile trip were the police in the towns and cities they passed through. Police provided protection the whole distance, as well as food and shelter when several churches failed to provide accommodations as promised.

Therefore, he said, he felt confident the U.S. Park Police who were escorting the group across the bridge would protect their memorial until they could arrange through Congress to have it placed at the cemetery.

Sgt. Rob McLean, a Park Police spokesman, said that the caisson and memorial were taken to a lot where police cruisers are kept and that it was secure there. He said they are required to hold any abandoned property for 60 days to give the owner time to claim it.

“In a high-profile case like this, we are unlikely to destroy the property at the end of that period,” he said.

The group members had played mostly rock-and-roll music as they pulled the stone to Washington. Yesterday, they chose an ethereal composition that included drums, hand cymbals and chants, recorded for them by some Buddhist nuns and monks who had walked with them for several days. As the caisson was pulled onto the flatbed tow truck, Randa reached inside and turned on the tape.

As the truck rumbled down the bridge and out of sight, the music could still be heard. “Bye-bye, sweet stone,” said Jim Goodnow, one of the core team who pushed and pulled the stone the whole distance. Around him, others wept.

Randa told people in the dispersing crowd to write to their representatives in Congress to demand the stone be allowed in the cemetery. “We’ll be back to finish this,” he said. “Come back and join us then.”

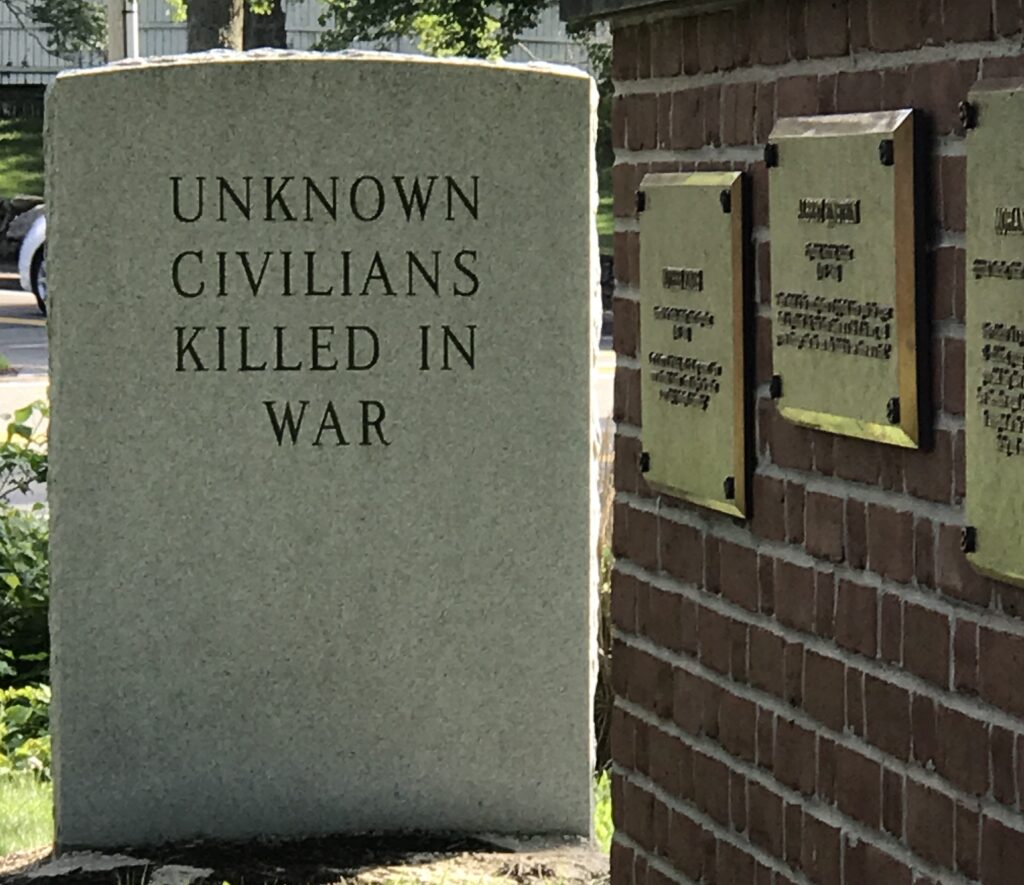

It’s quite a sight: A dozen people, huffing and puffing like oxen along the roadway in a hand-grip yoke arrangement as they pull a 15-foot-long caisson on rubber tires, its cargo a 2,000-pound granite memorial stone carved with the words, “Unknown civilians killed in war.”

A group of people connected with the Peace Abbey in Sherborn, Mass., came up with the project, known as Stonewalk, to honor these often forgotten casualties of war. Volunteers are walking the stone from Massachusetts to Arlington National Cemetery, where it will be offered as a gift. The group hopes that it can be placed outside the amphitheater near the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

As the war in Kosovo made clear, many civilians die in war. While soldiers are lauded with patriotic honors for their suffering, the recognition of civilian casualties too often gets intentionally lost in euphemistic creations like “collateral damage.”

Unless they’re useful as propaganda fodder, no one really wants to think about civilian casualties. They are either a horrible mistake or a moral embarrassment.

In the techno-war atmosphere of Vietnam, civilian bodies were used to improve the numbers. According to J. William Gibson, author of The Perfect War, “War-manager pressures for high body counts led to both systematic falsification of battle reports . . . and systematic slaughter of Vietnamese noncombatants.”

In his memoir Happy Hunting Ground, Martin Russ puts it in more grim terms: “It’s too much to expect an American just out of Hick City High to distinguish between guerrillas and civilians; they all look alike, they all dress alike, they’re all gooks.”

That, sadly, is the nature of war. At the level of the killing, despite all good intentions on the diplomatic level, there are simply no rules. The killing of innocents is a given.

In the Philadelphia area, members of several veterans groups and others are helping to pull the stone. If all goes well, they will be walking through the Downingtown-Coatesville area today and tomorrow.

Public reception has been quite positive. The police chief in Plainfield, N.J., for example, took the entire Stonewalk crew out to dinner.

What exactly will happen when the Stonewalk caisson reaches the gates of Arlington National Cemetery is not clear. It is hoped that the simplicity of the stone and its nonpolitical message will not be seen as a threat to national security or somehow a dishonor to those in uniform who died in our wars.

The Stonewalk project is not pointing a finger – it is simply acknowledging an indisputable fact.

John Grant is president of the Philadelphia Chapter of Veterans For Peace.

A. Civilians die in war as surely and as finally as any soldier. They also die from the consequences of war: shattered infrastructures, poisoned water, abandoned land mines, and other ordnance. Civilians deserve to be remembered. By honoring slain civilians, we understand and acknowledge the gravity of war and the full extent of its cost. With that acknowledgment comes an even deeper reverence for those in or out of uniform who paid the cost with life itself. The victims offer us an opportunity for reflection and transformation. Acknowledging what has transpired, we may yet imagine alternatives for a better century and weave an intricate web of loving-kindness. In the words of poet Stanley Kunitz, “To whom can one pledge one’s allegiance except to the victims?” That is, to those who speak in silence on behalf of our children and of ourselves.

A. Simple acts bring healing. The placing of this simple stone in a quiet space within the Arlington cemetery may open up space within the heart. Those who visit will be moved by what they see: the sea of headstones, the stately somber buildings, this simple memorial. And when they leave, the memory of this place will help them to renew their commitment to those ends desired by soldiers and pacifists alike: freedom, justice, and peace. Soldiers and civilians die together. At Arlington National Cemetery, together, may we remember them.

A. Over 200,000 Americans are buried within the grounds of Arlington Cemetery’s 612 acres, including generals, soldiers of all ranks, presidents, politicians, and civilians. Arlington National Cemetery is primarily a burial ground for the military, but contains memorials to civilians as well. One of the more recent is the Memorial to the Challenger Space Shuttle victims, which contains the combined remains of the seven crew members, including Christa McCauliffe, our nation’s first civilian teacher to be launched into space.

A. The Memorial Stone was offered as a gift of conscience by the Peace Abbey and Stonewalk was the 500 mile, 33 day journey to bring this gift of honor to Arlington National Cemetery. There are any number of places at Arlington National Cemetery for the Memorial Stone, – though and the best location would be outside the amphitheater near the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Two of the co-sponsoring organizations, Veterans for Peace and Women’s Action for New Direction, worked with legislators to obtain an Act of Congress allowing the Memorial Stone to be placed in Arlington. So, while approval has not yet been received, we are proceeding with full confidence that our government will someday honor the civilian victims at Arlington National Cemetery. Why? Because it is needed to reflect the true cost of war.

A. The Memorial Stone is for Unknown Civilians Killed in War honors those who lost their lives throughout the globe over the centuries. This includes all armed conflicts fought without the official declaration of war, as in Korea and countless other conflicts throughout history. It is important to remember that the destruction of wars continues for years after the hostilities cease through direct means such as abandoned land mines as well as the diseases and despair from shattered families and destroyed infrastructure.

A. Muhammad Ali dedicated his life to promoting world peace and social justice and has made numerous international peacemaking trips since his days as the heavyweight champion. He unveiled the Civilian Memorial stone on May 4, 1994 on the grounds of the Peace Abbey.

A. Just as there are remains of soldiers that are not able to be identified after a conflict, civilians have been killed without their remains being identified. Families are displaced, and the survivors may not know the whereabouts or details of their deaths. Mass graves of unidentified bodies exist all over the globe. The Memorial Stone provides a place of reflection in their honor.

A. No civilian remains are interred with the Stone, which stands as a memorial to civilians killed in all wars throughout the world.