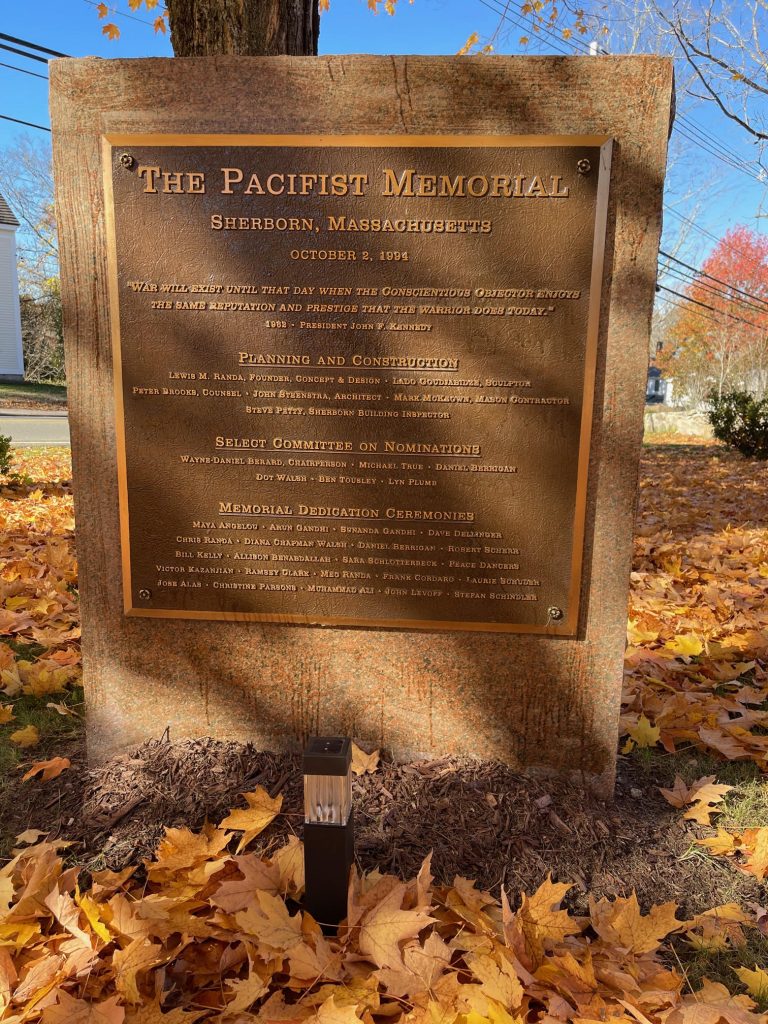

THE PACIFIST MEMORIAL

DEDICATION of THE PACIFIST MEMORIAL

By J. William Semich, TAB Columnist, October 2nd, 1994

“As I look up at the statue of Gandhi and start to read the inscriptions on the Walls of Names that surround the statue, a distant memory begins to stir inside me.

I remember that Gandhi and his teachings used to be a very big deal for me and for hundreds of thousands of others in my generation. I remember when, in the distant past, I read the works of Gandhi and of Martin Luther King and tried to live a life based on their ideals. It dawns on me that I had even once thought of myself as a “pacifist” and had acted on those thoughts for nearly a decade.

How is it, I am asking myself, that I had forgotten all that?

And so, I begin to think thoughts and feel feelings that had somehow gotten buried over the years, buried under real-world problems like graduate school, careers, finding and fixing and paying for a home, raising kids, paying bills, and the other daily details.

I remember 1961, marching across the Potomac—along with thousands of pacifists, religious leaders, and other naive young idealists like me—carrying ‘Ban The Bomb’ and ‘Student Peace Unions’ signs, hoping and praying we could convince President Kennedy to stop the open-air testing of nuclear weapons, then to ban nuclear weapons forever.

Idealistic? Sure. But Gandhi proved that it’s the idealists who can change the world.

Today, with open-air testing banned for decades, we don’t worry about nuclear fallout. Back then, we had nuclear fallout around us all the time—in the air we breathed, in the food we ate, in our bones, in the bodies of unborn babies, and in everybody’s mother’s milk. Strontium 90, as they called it, is a deadly nuclear material with a half-life of 28 years that, like lead, replaces calcium in your bones. It was there thanks to the arms race between the US and the Soviets.

And I remember how great it felt when we won that one, when President Kennedy first announced a temporary ban and then a permanent ban on atmospheric testing.

Today, as I stand under Gandhi’s statue, I see Martin Luther King’s name on the Wall of Names, and I remember something else I had forgotten: the Freedom Rides.

Like the night in 1962, when I was in a young college professor’s living room watching two African American students (gently) pummeling and shouting at a fellow black student who had gone limp on the floor in the classic pose of passive resistance. I had forgotten—but now I remember—this, my first lesson from the nonviolent black civil rights group, the Students Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, in Gandhi’s and Martin Luther King’s teachings on the use of nonviolence to change unjust laws.

Now, the rain lets up a little here at The Pacifist Memorial, and I watch as the ceremony finally begins with spirituals and gospel songs. The songs bring me back to another night long ago, after a full day of “sitting in” (black and white together) at the many whites-only restaurants that then lined the highway between Baltimore and Washington, DC, trying to use Gandhi’s teachings to peaceably force them to serve all races of people. That night, we all gathered at the Baltimore AME church to celebrate our victory. No one had been arrested, no one had been asked to leave, and some had actually been served in the restaurants. We all joined hands in the church to sing spirituals, ‘We Shall Not Be Moved’ and ‘We Shall Overcome,’ and, right then, as we crossed our arms and held each other’s hands and swayed to the music, we really believed it.

But it had a larger sacrifice than all that. It took the assassination of President Kennedy late in 1963 to shame Congress into finally passing the Civil Rights and the Voting Rights Acts of 1964.

I remember all this—and more, much more—as I stand there in the rain looking at Gandhi. I recall that Gandhi himself had died at the hand of an assassin. And then, I see John Lennon’s name on the Wall and his “war is over if you want it.”

I remember how I never could reconcile myself to that unexplainable tragedy—the violent haphazard death of John Lennon, the peace lover, the gentle man, the metaphor for my generation.

Whew! These are powerful memories of a tragic era in our national consciousness, memories and feelings I had successfully held in check for 20 years, now rushing back in a jumble of emotions here in the rain at The Pacifist Memorial.

What is it about a statue and these walls of brick—the image of Gandhi, these names, these quotes—that can generate such strong emotions?

I begin to understand. You’ve seen those pictures of tearful veterans with their hands pressed against the names carved on the walls of the Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial. For me, The Pacifist Memorial in Sherborn has just that effect. It is more—a whole lot more—than just a statue and list of names with important quotations.

It is a gathering place for memories, a lens that magnifies and refocuses our emotional recollections of forgotten friends, of fallen heroes, of times long past, of innocent lives cut short, and of now-distant ideals. A place to relive, to remember, to mourn, and to reconcile.”